Who needs artists

Who needs artists? Rise in works made by artificial intelligence raises real questions for the art market A new portrait produced by an algorithm, expected to sell for around $10,000 at Christie’s this month, prompts new debates over authorship

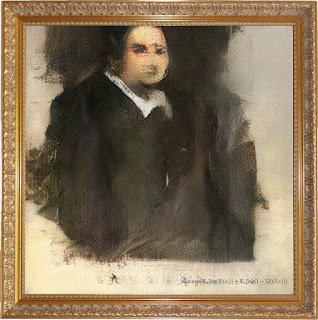

Portrait of Edmond Belamy was created using an as-yet-unrevealed source code and hits the auction block this monthCourtesy of Christie’s

This October in New York, Christie's will be the first auction house to sell a work created by artificial intelligence (AI). The 2018 painting, a hazy portrait of a well-fed clergyman, possibly French, hailing from an indeterminate period in history, is expected to fetch between $ 7,000 and $ 10,000. His name, according to the work's title, is Edmond Belamy.

Even more curious is the signature scrawled on the bottom of the canvas, which reads: min G max D 𝔼x [log (D (x))] + 𝔼z [log (1 - D (G (z)))], and refers to the algorithm, or generative adversarial network (GAN), that produced the work.

Signing the canvas with an algebraic formula May be a mere marketing ploy, but the sale of AI works in general is raising important questions about authorship. If a work is conceived by a human but created by a machine, who owns the copyright? And what happens in a dystopian, but potentially real, scenario where there is no human interaction at all? Could an AI then enjoy copyright privileges? After all, Sophia the AI robot was given citizenship status in Saudi Arabia last year.

Who holds the keys to the code?

As with literary works, a source code automatically qualifies for copyright protection under UK and EU laws - the copyright holder for something that has effectively been created by a machine. As the US artist and digital art collector Jason Bailey says: "The process of coding generative art [is] similar to painting or sketching."

However, there is an important difference between the Belamy family collection and other images in the fictional Belamy family collection. Pierre Fautrel, one of the three members of Obvious, the Paris-based collective behind the paintings, says that they are not to copyright their code. According to Dehns, a law firm specializing in patents and trademarks, worldwide patents can cost as much as £ 10,000.

The question is whether Obvious will freely share their source code with the world at large. For the moment, the answer is no. "Once we have created our second collection, we will openly publish the code to the Belamy family collection," Fautrel says.

Fellow member Gauthier Vernier sees the portraits as a collaboration between the algorithm and Obvious. "In that sense, you could say the copyright should be shared, but there is no legal framework in which to consider the algorithm as an author," he says.

What could AI law cover?

The Belamy pictures were produced using algorithmic or two parts: a generator and a discriminator. Obvious fed the system with a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th and 20th centuries, crucially all out of copyright. The generator is one that has been created by the generator.

The portraits are not as good as before, as Vernier explains, the algorithm will not produce the same result twice, even if trained on the same dataset, so each painting is unique. "The fact that we use a physical medium that we hand-sign ensures that the works can not be replicated. So, we focused on protecting the final product, not the algorithm, "he says.

The market for AI works is still very much in its infancy, although slowly gaining momentum. As it continues to grow, the question of copyright versus open source could become a real sticking point. "If we start seeing works at thousands of thousands or thousands of dollars, does that shut down open-source in these communities?" Bailey says.

Similarly, as Tim Maxwell of the London law firm Boodle Hatfield points out, developments in art generated by AI are "pushing right up to the edge of what copyright laws currently cater for". The biggest issue, Maxwell says, concerns the "human input element" of the work. "Until now, computers have been the means of producing the work, rather than the creative origin - something they could conceivably become," he says, adding that although we are not at that point yet, "Very difficult question".

For now, at least, it seems that autonomy is squarely in the hands of humans. But for how long?

After publication, The algorithm is the GAN, so there is no question about patenting it because it is common knowledge. We did not invent it, Ian Goodfellow did. We wrote the code, which could be patentable, but very expensive and arguably useless, so we decided against it.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your response

Kind regards Pierre